IoT Day Copenhagen – What kind of future do we want to live in?

Written by Inda Memic

“The door refused to open. It said, “Five cents, please.”

He searched his pockets. No more coins; nothing.

“I’ll pay you tomorrow,” he told the door. Again, it remained locked tight.

“What I pay you,” he informed it, “is in the nature of a gratuity; I don’t have to pay you.”

“I think otherwise,” the door said. “Look in the purchase contract you signed when you bought this conapt.”

…he found the contract. Sure enough; payment to his door for opening and shutting constituted a mandatory fee. Not a tip. “You discover I’m right,” the door said. It sounded smug.

From Ubik, by Philip K. Dick. Published by Doubleday in 1969

While the quote in Ubik was imaginary and futuristic in 1969 the basic idea is not far from today’s IoT development. Connected devices are developing much quicker than the legal mechanisms available to protect the technology and their users. Although, we don’t yet have doors that refuse to open because of a missing fee that was signed for in the initial contract, we have Alexa and Google Home who gladly answer our questions while collecting and storing our data – with our consent – even when we can’t see it. But, why is that a problem?

When data collection and use is invisible to us – the end users – we can’t control where our data flows, who will use it, and more importantly what it is used for. Now imagine a friend who knows everything about you, and who chooses to use this information to make money, say by manipulating your decisions to benefit them. And imagine the moment when you realize that your friend is the kind of morally bankrupt person who used your information in ways that you would never have imagined or consented to. What would you do? Whom would you hold responsible?

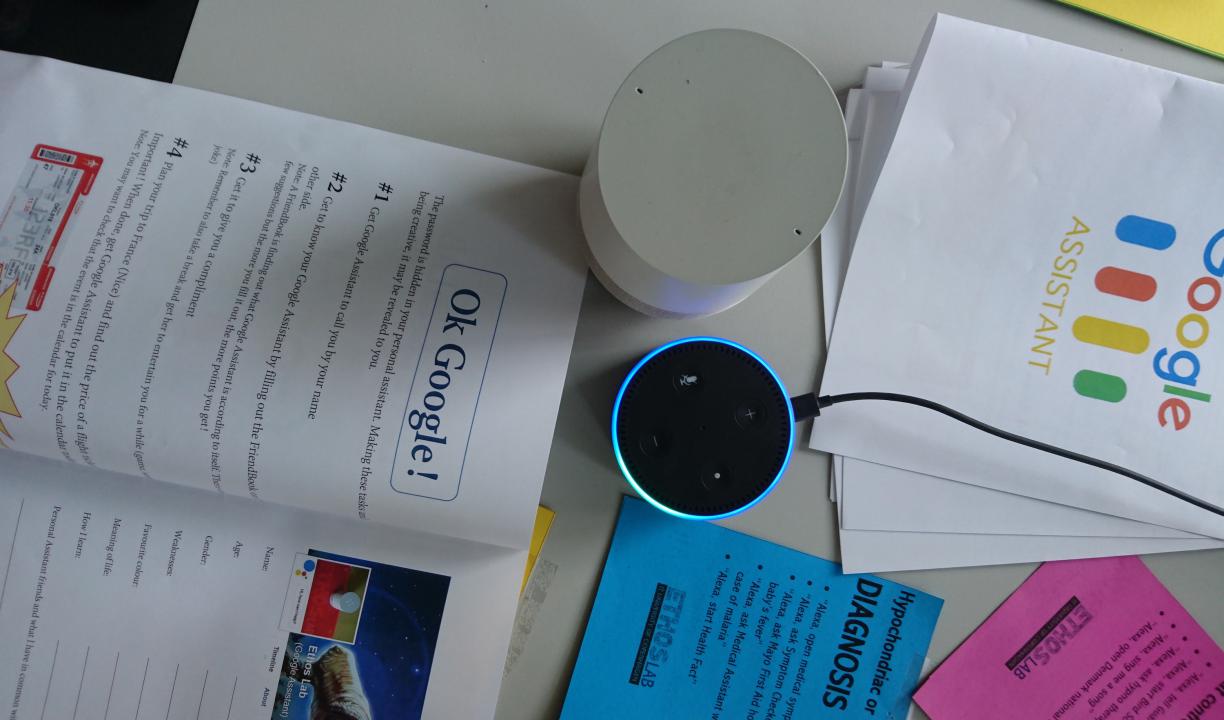

Such ethical considerations were the pivot of IoT day. In the opening talk, researchers Irina Shklovski and Rachel Douglas-Jones presented the VIRT-EU project – and its intention to support developers in reflecting on the ethical decisions that they make as part of the design and development process for future devices. The audience was introduced to several recent IoT manifestoes in which developers show increasing concerns about ethics.

Subsequent interactions with Alexa and Google Home enabled first-hand experiences with the devices. The participants asked various questions and were amazed of the kind of responses they received. One participant, a student from KDAK, asked Alexa ‘Hi Alexa, what should I do with my life’ to which Alexa answered that she doesn’t know. Another participant asked both Alexa and Google Home whether they are connected to the CIA (Alexa said that she only works for Amazon; Google Home said that no government entity has direct access to the data because privacy and security is of great concern), while others asked Alexa if she was recording us (and yes, she was sending information back to Amazon).

Asking questions in various ways made us all reflect on the nature of the responses we received from the devices that have come to inhabit our environments. Who are the people behind the technology? And, how close are we to having a door that will insist on charging those 5 cents for every entry?